Shah Mat

Scroll Down to Read

“Shah Mat. That’s Persian for ‘the King is dead.’”

Cousin Ukban knocked over my King piece and laughed in triumph. “Can we play again?” I asked him, for the latest time.

“You won’t win,” said Ukban, but he began rearranging the pieces in their neat, opposing rows.

We were playing Shahtranj, the Persian Game of Kings.

I considered the board. Eight squares by eight squares, this was a game of numbers. I advanced a Sarbaz, an infantryman, on the leftmost flank.

“Interesting move,” said Ukban, knitting his brow. He umped forward a Pil - an elephant - with its two tusks and long trunk carved on the front. “The Pil can jump diagonally over other pieces. That makes it the stronger piece.” He warned.

Too focused to respond, I brought forward my left-side Rukh, the Persian word for chariot. “The Rukh can travel the length of the board,” I reminded him.

“But only in straight lines,” he responded, and zagged forward with the immense Pil.

“Straight lines are better,” I reasoned, as we each advanced a Sarbaz. “They’re easier to see clearly.”

“You need to learn to see diagonally,” said Ukban, and the Vizier made his crooked move into the front rank.

I tried to bring forward my second Rukh, but it was too late. “Shah Mat,” Ukban repeated, two moves later. “And no, I’m not playing again, you’re not good enough to be fun. Anyway, we men need to go to synagogue.”

And like magic, Rustam was there. “Come, young Lord Josiah,” he told me, “the ladies are out in the garden. Would you like to play with your Cousin Rachel?”

I nodded and followed him out into the courtyard. By the tinkling fountains beneath the quinces and persimmons, I found them speaking to the animals.

“The lamb says, baa,” said Aunt Tamar. “What does the little lamb say, Rachel?”

“Baaa!” said Rachel excitedly.

“Baaa!” said the little lamb.

“Look!” said Mother. “Here is Josiah. What does the little donkey say, Josiah?”

I took in a deep breath. “Hee-Haw!” I brayed.

“Hee-Haw!” brayed the donkey, and Rachel laughed. All of the ladies were laughing too.

“Want to ride the donkeys?” I suggested. Rachel giggled and agreed. Mother helped me onto the back of my favorite little grey donkey, and Aunt Tamar placed Rachel on a speckled one. We rode the docile creatures in a small circle around the ladies of our family, who applauded.

“Mother,” called Cousin Ukban from inside the house, “Mother, can you come help me, please?”

“I’ll be right there, Jacob,” she answered. “Please excuse me, ladies.” Then, turning, she said, “come, Lada,” to the yellow-haired slave with the crooked smile.

“Da, I mean, yes,” said Ladaa. And then Rachel and I were alone with Mother and Grandmother and the animals.

Grandmother smiled at Mother. “Don’t those boys remind you of their Fathers at that age?”

Mother blushed. “A little, yes.” She was cooing to David, who seemed to be sleeping again.

“I’ll never forget when you first saw them. When they came over to meet your Father for the first time. Young Judah, so tall and strong with his fine red beard; Zakkai with his nose in a scroll. You were setting the table with that heavy wine jug.”

“No, Mother,” my Mother corrected Grandmother, “Zakkai wasn’t reading. He was explaining a point of Talmudic law to Judah.”

“So he was, darling, so he was,” said Grandmother. “But the instant he locked eyes with you, he said…”

“‘Lower your pitcher, and I will drink,’” remembered Mother. “And, learned, fool young thing that I was, I answered him…”

“‘Drink, and I will also water your camels,’” recalled Grandmother.

The camels brayed at that, and we all laughed.

“The reply of Rebecca to Eliezer,” I realized.

“That’s right, Josiah,” Grandmother affirmed.

“Then what happened, Aunt Hannah?” asked Cousin Rachel. “Did you marry Uncle Zakkai?”

“Well, you see I couldn’t, not yet,” said Mother. “I needed my Father’s permission, and my Father…”

“Had already promised to marry her to your Cousin Hasdai,” Grandmother finished. Rachel shrieked and sucked in her breath, but I had already heard this story a thousand times.

“Why?” asked Rachel. “Why would he want you to marry someone like that? Cousin Hasdai is so mean! He called me a ‘smelly little girl,’” she remembered, tearing up.

“That sounds like him,” said Grandmother. “That mound of vulture’s droppings. Oh, don’t look so scandalized, Daughter. You know what he is as well as I do. Well, you see, Judah and Zakkai’s Father - your other Grandfather, children - was the Exilarch Ahunai, but when he died suddenly, Hasdai’s Father Natronai was appointed Exilarch, and your Fathers became his wards.”

“What are wards?” Rachel asked.

“It means,” explained Mother, “that they were raised like Brothers to Hasdai. And although Judah outshone him with his strength and courage, and Zakkai in intellect and kindness, Hasdai was always the one preferred - with presents and honors.”

“And your Father,” Grandmother told Mother, “very much wanted to be Gaon of Sura after my Father - that’s your Great-Grandfather, Josiah, the Gaon Kohen-Tzedek ben Abimai - who the scholars loved because he insisted on speaking Hebrew, not Aramaic. Well, Sheshna never got that honor, that had to wait for your Brother, Amram. That’s when I said to him, Rav Sheshna, this is just like what happened when we met, thirty years before.”

“What happened when you met your Husband, Great Aunt Sarah?” asked Rachel.

“Oh, this was a long, long time ago,” said Grandmother, with a wistful expression. “A long, long time ago. This was in Baghdad in the days of Harun al-Rashid. How beautiful it was in those golden days, before the siege.”

“The siege?” I asked.

“The Great Siege of Baghdad,” reminisced Grandmother. “During the war between the Caliph Harun’s Sons, Muhammad al-Amin and Abdallah al-Mamun. Al-Amin ruled from Baghdad but al-Mamun rallied the support of the Khorasanians, the old pillars of the House of Abbas. Nothing could stand in the way of his Persian general, Tahir ibn al-Husayn, the Ambidextrous, the One-Eyed. And my, my, how powerful Tahir’s family has grown! Do you know, we were under siege for eleven months? Almost a year.”

“Was it scary?” asked Rachel.

“Oh, child,” said Grandmother, “we were lucky to have had enough to eat. You see, Josiah, your Grandfather, Rabbi Sheshna, was a great singer like your Uncle Amram, and he had a special connection to animals, just like you.”

“Like me?” I asked, as Cousin Rachel looked at me with appreciation.

“Josiah and I talk to the animals,” Mother explained. “Just like we were doing with you.”

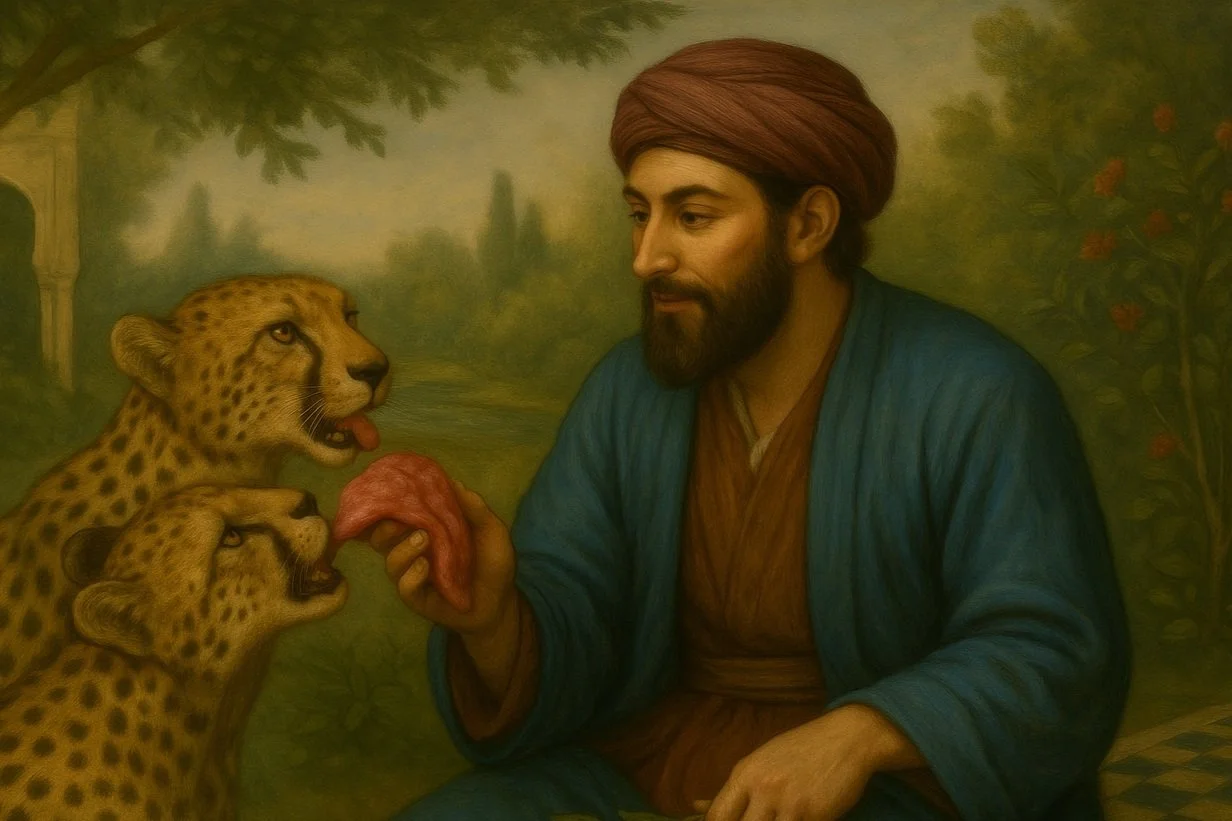

“You can talk to animals too, can’t you princess?” said Grandmother. “Well, my Sheshna, he got the job of keeping the Caliph’s great menagerie of animals in the Round City of Baghdad. Like Noah on the Ark, he knew what each one liked to eat. He brought fresh meat to the lions and leopards, old meat to the jackals and hyenas. He fed tender shoots to the antelope and hardy branches to the giraffe. He coaxed the elephant to eat with gentle persuasion and risked his life more than once to feed the blind Rhinoceros.”

“Once, when a lion escaped, he charmed it before it attacked a visitor, who turned out to be the musician, Ishaq al-Mausili, who used to play shahtranj in the palace with the Caliph al-Amin. Your Grandfather, as a Jew, wasn’t allowed inside the palace. Ishaq taught your Grandfather a special Arabic maqam - a haunting melodic mode - to sing if he ever had to warn them in case of danger.”

“One day, he was feeding the Caliph’s hunting cheetahs when he chanced to overhear a spy in the garden, who said that today Tahir’s men would be attacking the Round City.”

“Straight away, your Grandfather sang the maqam.”

“Ishaq tried to warn the Caliph, but he was too engrossed in the game. ‘Never mind,’ said he, ‘I am about to checkmate my opponent.’ A few minutes later he lost everything to his Brother, al-Mamun, and to One-Eyed General Tahir. But of course, this brought both your Grandfather and the musician under suspicion by old One-Eye, and he had them summoned before him.”

Just then baby David awoke and began to cry loudly.

“There, there baby,” said Mother. “Could you help me, Mother? We’ll have to finish the story later. Stay here and play with your Cousin Rachel, Josiah, I’ll send Aunt Tamar or that Lada girl out to watch you.”

They went inside and I was alone with Rachel in the Garden. Citrons and persimmons ripened temptingly overhead, and I plucked an early red pomegranate off the tree and split it open for Rachel.

“Look,” I told her, “the pomegranate is the only fruit where the seeds are sweet and red, and the fruit is yellow and bitter. Did you know each pomegranate has 613 seeds, like G-d’s commandments to Israel?”

She plucked a few of the plump red seeds. “Be sure not to eat the bitter yellow!” I warned her. “It’s really gross!”

“Mmmm!” said Rachel. “It’s sooo good!”

We walked deeper into the Garden, past the cooing doves, the honking geese, the proud peacock and his brood of drab peahens.

At length we stood under the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge. Rachel looked at me sideways, her cheek dappled in sunlight-and-shadow.

“Do you know,” she asked me, “what the difference is between a boy and a girl?”

“Of course,” I said uncertainly. “Girls have long hair. Boys have short, but after their bar mitzvah, they can grow a beard on their faces.”

“No, silly.” Rachel looked up at me with her big almond eyes. “Only girls can have children. But only when they’re married to a boy.” She looked at my face pensively. “Father said I could marry anyone I want when I grow up. As long as he’s Jewish, Father said.”

“My Father said the same thing,” I told her. “Mother said to be sure it’s someone smart and nice.”

“When we grow up,” said Rachel, “I want to marry you.”

I blushed. “That would be nice,” I said. “Then I could be married to my friend.”

“Yes,” she said. “You have to promise. I don’t want to marry a stranger. You have to promise to marry me.”

“Okay,” I said. “I promise.”

Suddenly, I heard the sounds of men coming into the anteroom.

“I’m sure he’ll be delighted to see me,” said a strange voice.

“I’ll have to ask you to wait here,” said Rustam. “The gentlemen haven’t returned from synagogue yet. May I offer you same tamarind sharbat as you wait?”

Then, “Children?” as he stepped into the garden. “Come here, children, you must come inside.”

“Wait.” I grasped her hand. “Do you promise to marry me, too?”

“I promise, I promise,” she said.

“There you are, young Master!” For an instant, I started, but there was no way he had seen me holding Rachel’s hand. “Get your Cousin inside, Josiah, your Fathers have an unexpected visitor.”

I brought us through a side door. I heard the voices of Father, Uncle Judah and Uncle Amram at the front entrance. They paused as Rustam’s calm voice said something inaudible, than Uncle Judah shouted something distorted by the hallway.

“Hsss,” said Cousin Ukban, grabbing my arm.

“Thank you, Lada, that will be all,” said Ukban, too quickly. His voice, just for a moment, had a strange edge — almost embarrassed, or… something else. “Lada, go watch my Sister,” he added, not meeting her eye. “Josiah and I will play shahtranj.”

Lada gave a small curtsy and left without a word. Ukban stared after her until she was gone, then blinked as if remembering I was there. “I thought I was no fun to play with,” I reminded him. “Shhhh!” he hushed me.

His silk robes swished as we walked through the mazelike corridors, and he set up the shahtranj board next to a lattice window.

“He waylaid us, Zakkai, like a highwayman,” Uncle Judah was saying.

“Remember, Brother, to him it’s not Yom Tov,” Father said reasonably.

“That’s very much the question at hand,” said Uncle Amram. “Be that as it may, your Brother and I can’t be here when you speak with him. His matter is before the Kafri Beit Din, and that is your responsibility, O Dayan al-Bab, Husband of my Sister. He cannot invoke the authority of the Sura Academy or the Head of the Exile in the resolution of this matter.”

As if waking from slumber, Ukban pushed forward a Sarbaz from the middle ranks, and I moved forward with my horse, Faras. “Hush!” he said again, and the voices of my Uncles receded down the hallway. “O My Master, Dayan al-Bab,” called Rustam, “I present to you Rav Benjamin ben Moses, lately of Nahawand, scholar of the Karaites.”

“Just Mar Benjamin, if you please, good Rustam, we do not have Rabbis among the Karaites.” I heard the stranger say. “Greetings, oh Dayan al-Bab. Your Cousin Hasdai said this would be a good time to find you here, but I find myself early for your return. I hope I do not find you discomfitted.”

“As long as you do not leave me so,” said Father. “Did he tell you that? Hmmm. I had wondered at his lateness to the morning’s service. What brings you here, Mar Benjamin?”

I advanced my elephant again and captured Ukban’s Vizier. He seethed with displeasure, but said nothing.

Continue the Journey

Sneak peak at more of the adventures in Josiah’s quest to save Geonic Age Jewry.

-

In the jeweled halls of Baghdad, a deadly roar interrupts diplomacy — and a father races to save his daughter. Read the excerpt

-

As Kiev burns under a Norse siege, Josiah races through the city to gather his bogatyr allies and rescue a runaway princess… but a Valkyrie gets there first. Read the excerpt

About the Art

If you'd like to learn more about how the pictures were created, click here.